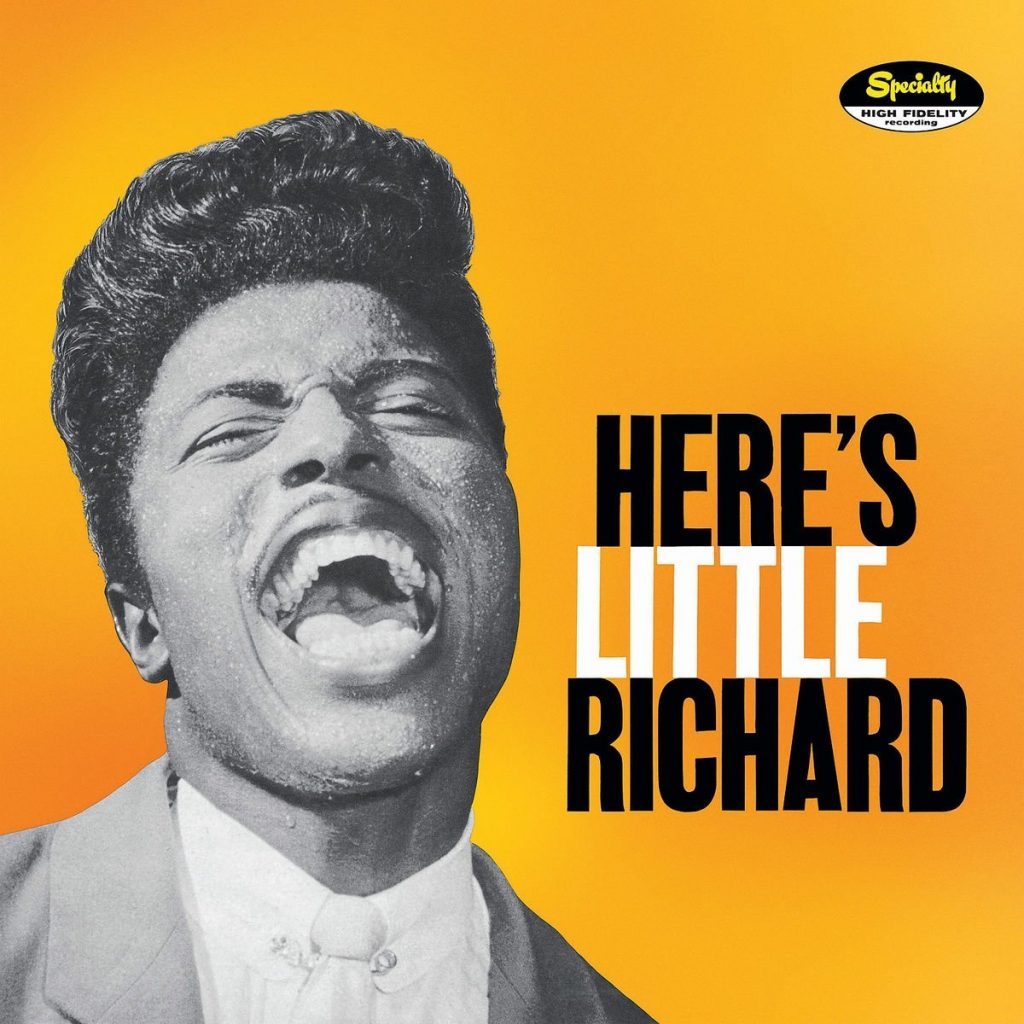

The first words of Richard Penniman’s debut album, Here’s Little Richard, are seminal. In the years since the song was released in 1955, they have come to define the explosive birth of rock and roll music into the world and have been quoted countless times by countless musicians. Also, the first words of Here’s Little Richard are, in fact, not words at all, but some kind of inspired vocalized scat of an imaginary drumbeat. Penniman was probably the last person to think that, in writing down the phrase “A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-wop-bam-boom”, he was in fact writing musical history that would be remembered for decades and decades to come. It isn’t just the words that are sung, but the way the singer sings them. Elvis Presley and Pat Boone each tried their hand at “Tutti Frutti”, the song about which I’ve been writing. Presley’s is pretty good, but I feel that even attempting to do something Little Richard did first is setting yourself up for failure. Here’s Little Richard, an album made up of Little Richard’s previous singles and some new songs, is an explosive record of sheer rock and roll energy, and time has not dulled its razor-sharp edge.

Richard Penniman’s life was lived serendipitously in the thick of the musical developments that would inevitably lead to the explosion of rock and roll in the 1950s. Growing up in a religious family in Georgia, Penniman was exposed to gospel music at a young age, and he especially admired performers such as Sister Rosetta Tharpe. After meeting Tharpe and opening one of her shows at the age of 14, as well as learning to play the piano upon hearing the record “Rocket 88”, Penniman began to pursue music as a career. He performed in countless settings, each one adding a little more to his increasingly impressive resume: a traveling voodoo show, gospel concerts, drag shows, the Atlanta club scene. Eventually, Penniman began to form his own distinctive sound, combing gospel and rhythm n’ blues. Nevertheless, his early recordings failed to generate any kind of interest. The turning point came while Penniman, recording with producer Robert Blackwell and Fats Domino’s band, introduced a risqué song called “Tutti Frutti”. Needless to say, the song was a hit in 1955, and the rest, as we know, is history. “Tutti Frutti” was followed by four other hit singles during the next year or so, during which time Little Richard became something like a rock god.

Here’s Little Richard is something like a victory lap for Little Richard. Here, we have the six singles that made him a star: “Tutti Frutti”, “Long Tall Sally”, “Slippin’ and Slidin’”, “Ready Teddy”, “Rip it Up”, and “She’s Got It”; as well as six new songs. It all begins with those famous words we all know and love, and it never slows down from there. One caveat of the early rock and roll of the mid-1950s is the reliance of many songs on the 12-bar blues format. Make no mistake, the 12-bar blues is a timeless and endlessly thrilling song structure, but many older songs can feel quickly dated as soon as the listener perceives its presence. What’s remarkable about Little Richard’s songs is that they all sit very firmly in the rhythm n’ blues tradition. There’s very little deviation from the 12-bar blues. Despite this, each song feels wonderfully fresh and unique, because Little Richard knew how to take a standard structure and make magic with it. Sometimes it comes from changing up the beat, as in “Slippin’ and Slidin’”. Mostly, though, it’s the performance that sells it. Little Richard’s style was considered harsh and aggressive in it’s day. And it still should be. I mean, listen to that. He screams into the microphone so hard, the track overloads and distorts. Less noticeable, but still important, is his piano playing. Listen to the piano in the introduction to “True, Fine Mama.” Those are some intense keys. The other musicians deserve their share of praise, too. I love the saxophone solos provided by Lee Allen and Alvin Tyler, as well as Edgar Blanchard’s iconic guitar in “Rip It Up”.

Little Richard was never quite as popular in his day as his contemporaries: Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, or Chuck Berry. Nevertheless, his influence is felt radiating throughout all of rock and roll music. Songs like “Ready Teddy”, “Long Tall Sally”, “Rip It Up”, and of course, “Tutti Frutti” have been covered by Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Wanda Jackson, and many others. Sometimes it’s almost as good as the original. But nothing compares to that burst of sheer energy emanating from Penniman’s mouth and hands. It’s easy to see how so much of rock and roll finds its origin point here in these raucous recordings. Richard Penniman just died earlier this year. He tossed the rock into the pond, and he lived to see the ripples spread out all the way to the edges and return again. There are not very many people who can lay claim to that, and there’s really only one proper response. You’ll find it recited in the beginning of this album’s first track.