Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil. Or so they say. The image of that lone, dusty man, standing at a crossroads at midnight, meeting the Evil One himself has become the myth and the legend, a legend that informed blues, rock-and-roll, and American Mythology as a whole for years and years afterward.

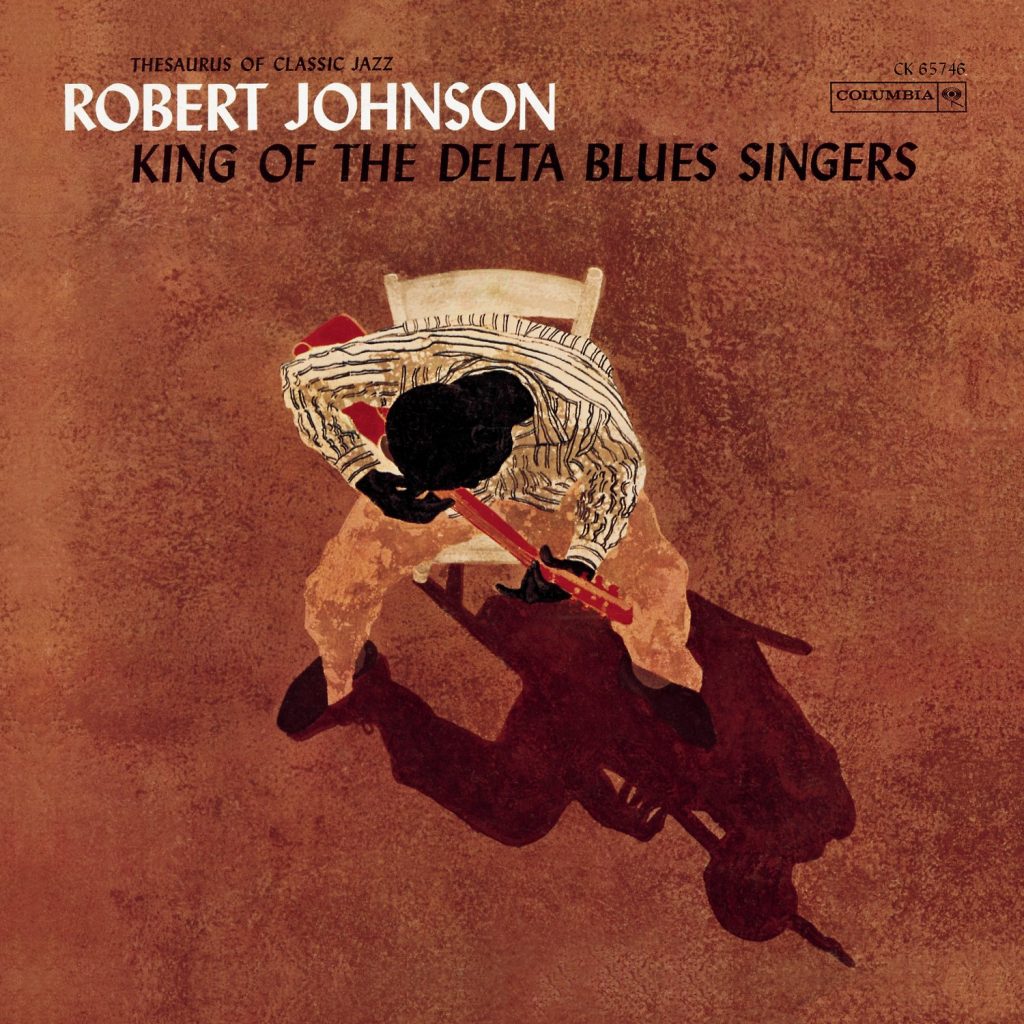

In 1938, John Hammond of Columbia records went south, looking for the mysterious Robert Johnson, supposedly the best guitarist in the land, to perform for a concert at Carnegie Hall. Upon making some inquiries, Hammond came to learn that Johnson had died earlier that year. Soon, Columbia acquired the few recordings Johnson had made during his lifetime, and, a few decades later, released them under the title King of the Delta Blues Singers. And then the legend truly began. The record had an enormous impact on the up-and-coming musicians of the day, including Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and Keith Richards, and it shows. King of the Delta Blues Singers has something of a double significance. It has a significance for the time it was created, in 1937, when there was no such thing as an “album” and recording opportunities came few and far between for black blues musicians living in the American South. It also has a significance for the time it was compiled and released, in 1961, arriving at the cusp of rock music’s maturation, and the time when more and more musicians began to grasp the idea of the “album” as an intentionally grouped collection of songs. King of the Delta Blues Singers is technically not an album, but a compilation, but its influence is so magnitudinous that to exclude it would be a great sin. Countless reverberations in rock-and-roll music can be traced back all the way to that lone, dust-covered individual, standing at a crossroads at midnight, making a deal with the Devil.

In fact, it is just there at the crossroads that King of the Delta Blues Singers begins, with “Crossroad Blues”, possibly one of Johnson’s finest songs. These songs were recorded in rooms hastily converted to makeshift “studios” in San Antonio and Dallas, with ancient recording equipment at that. However, this does nothing to dim or cover up Johnson’s impeccable technique and style. He never fingers a string he doesn’t mean to, sliding with perfect precision up and down the neck of the guitar. The sparse, intense recordings always come fueled with an unstoppable drive that can be felt in the undertones of the music, driving at full speed down an old, dusty road in the deep south, always on the run from something clutching behind. The songs are reasonably brief, usually clocking in between two and three minutes, but Johnson always takes his time, never rushing through, just letting that drive carry him along as though it were a wave carrying the sound. Listen to the way that Johnson uses the high and low strings in “Me and the Devil Blues” to create melody and percussion at the same time – it’s like watching an ultrasound of rock-n-roll’s embryo kicking in the womb. In the 60s, when Johnson’s fame finally began to spread to mainstream white listeners, rockabilly and blues rock were already on the rise, but this recording of Johnson introduced a new standard of technical precision, intensity, and mood-setting to the blues rockers of the day.

Johnson’s voice is similarly unforgettable on this record. On account of the recording quality, the lyrics are rather hard to pick out, but they tend to cover the range of downtrodden topics that give the blues its name. What might surprise you when reading the lyrics is how Johnson, remaining underground for much of his life, wrote songs totally unaffected by expectations of decency at the time. Frequent references to the devil and sexuality (“Terraplane Blues”, “Come On In My Kitchen”) slip through, images that would inevitably become staples of the rock and roll scene. Ultimately, one cannot ignore that this tiny stone, when thrown into the waters, caused ripples that reverberated for decades and decades afterward. Johnson hardly knew anybody during his short life, and hardly anybody knew him, or even knew of him. Nevertheless, these few recordings form the rock-solid foundation of recorded blues and rock music that most of our industry is built upon today.

Coming up next:

Woody Guthrie – Dust Bowl Ballads (1940)

Comments are closed.